What Is Degenerative Disc Disease?

By Brian McHugh, MD | Featured on Spine Health

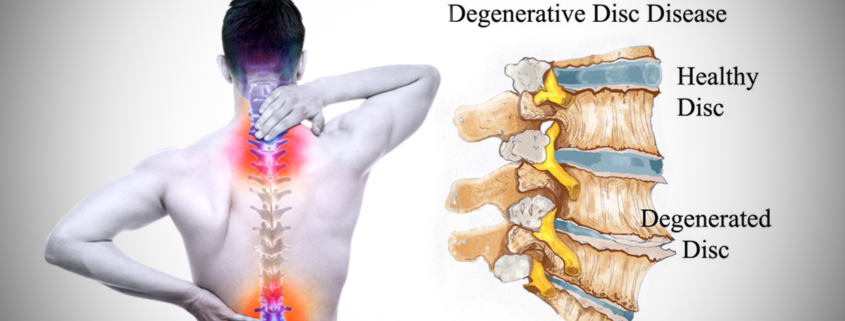

Degenerative disc disease is one of the most common causes of low back and neck pain, and also one of the most misunderstood.

Simply put, degenerative disc disease refers to symptoms of back or neck pain caused by wear-and-tear on a spinal disc. In some cases, degenerative disc disease also causes weakness, numbness, and hot, shooting pains in the arms or legs (radicular pain). Degenerative disc disease typically consists of a low-level chronic pain with intermittent episodes of more severe pain.

Painful disc degeneration is common in the neck (cervical spine) and lower back (lumbar spine). These areas of the spine undergo the most motion and stress, and are most susceptible to disc degeneration.

Degenerative Disc Disease is a Misnomer

The term degenerative understandably implies that symptoms will get worse with age. However, the term does not refer to the symptoms, but rather describes the process of the disc degenerating over time.

Despite what the name suggests, degenerative disc disease is not a disease, but a condition in which natural, age-related wear-and-tear on a disc causes pain, instability, and other symptoms. This condition usually does not result in long-term disability, and most cases can be managed using non-surgical treatment methods.

While it is true that disc degeneration is likely to progress over time, the pain from degenerative disc disease usually does not get worse and in fact usually feels better given enough time. The degenerative cascade degenerative cascade theory explains how this process works.

Disc degeneration is a natural part of aging, and over time everybody will exhibit some changes in their discs. However, a degenerating disc does not always cause symptoms to develop. In fact, degenerative disc disease is quite variable in its nature and severity.

This article provides in-depth information about aspects of degenerative disc disease based on commonly accepted principles, such as how a degenerated disc causes pain and common symptoms and treatments.

Causes of Degenerative Disc Disease Pain

A degenerating spinal disc does not always lead to pain or other symptoms. Because the disc itself has very little innervation, pain usually occurs when the degenerating disc affects other structures in the spine (such as muscles, joint, or nerve roots).

Pain associated with degenerative disc disease generally stems from two main factors:

- Inflammation. Inflammatory proteins from the disc space interior can leak out as the disc degenerates, causing swelling in the surrounding spinal structures. This inflammation can produce muscle tension, muscle spasms, and local tenderness in the back or neck. If a nerve root becomes inflamed, pain and numbness may radiate into the arm and shoulder (called a cervical radiculopathy in cases of cervical disc degeneration), or into the hips or leg (called a lumbar radiculopathy, in cases of lumbar disc degeneration).

- Abnormal micro-motion instability. The cushioning and support a disc typically provides decreases as the disc’s outer layer (the annulus fibrosis) degenerates, leading to small, unnatural motions between vertebrae. These micro-motions can cause tension and irritation in the surrounding muscles, joints, and/or nerve roots as the spinal segment becomes progressively more unstable, causing intermittent episodes of more intense pain.

Both inflammation and micro-motion instability can cause lower back or neck muscle spasms. The muscle spasm is the body’s attempt to stabilize the spine. Muscle tension and spasms can be quite painful, and are thought to cause the flare-ups of intense pain associated with degenerative disc disease.

What Happens in The Spine During Disc Degeneration?

Degenerative disc disease primarily concerns a spinal disc, but will most likely impact other parts of the spine as well. The two findings most correlated with a painful disc are:

- Cartilaginous Endplate Erosion. Like other joints in the body, each vertebral segment is a joint that has cartilage in it. In between a spinal disc and each vertebral body is a layer of cartilage known as the endplate. The endplate sandwiches the spinal disc and acts as a gatekeeper for oxygen and nutrients entering and leaving the disc. As the disc wears down and the endplate begins to erode, this flow of nutrition is compromised, which can hasten disc degeneration. As the disc goes through this process, the disc space will collapse.

- Disc space collapse. As a disc degenerates the disc space will collapse, placing undue strain on the surrounding muscles as they support the spine and shortening the space between vertebrae, leading to additional micro-motion and spinal instability.

These processes typically progress gradually rather than all at once. Endplate erosion and disc space collapse can add to spinal instability, tension in the surrounding muscles, and both local and nerve root pain.

Common Symptoms of Degenerative Disc Disease

Degenerative disc disease most commonly occurs in the cervical spine (neck) or the lumbar spine (lower back), as these areas of the spine undergo the most motion and are most susceptible to wear and tear.

The most indicative symptom of degenerative disc disease is a low-grade, continuous pain around the degenerating disc that occasionally flares up into more severe, potentially disabling pain.

Pain flare-ups can be related to recent activity and abnormal stress on the spine, or they may arise suddenly with no obvious cause. Episodes can last between a few days to several weeks before returning to low levels of pain or temporarily going away entirely.

Other common symptoms of degenerative disc disease include:

- Increased pain with activities that involve bending or twisting the spine, as well as lifting something heavy

- A “giving out” sensation, caused by spinal instability, in which the neck or back feels as if it is unable to provide basic support, and may lock up and make movement feel difficult.

- Muscle tension or muscle spasms, which are common effects of spinal instability. In some cases, a degenerated disc may cause no pain but muscle spasms are severely painful and temporarily debilitating.

- Possible radiating pain that feels sharp, stabbing, or hot. In cases of cervical disc degeneration, this pain is felt in the shoulder, arm, or hand (called a cervical radiculopathy); in cases of lumbar disc degeneration, pain is felt in the hips, buttocks, or down the back of the leg (called a lumbar radiculopathy).

- Increased pain when holding certain positions, such as sitting or standing for extended periods (exacerbating low back pain), or looking down too long at a cell phone or book (worsening neck pain).

- Reduced pain when changing positions frequently, rather than remaining seated or standing for prolonged periods. Likewise, regularly stretching the neck can decrease cervical disc pain, and taking short, frequent walks during the day can decrease lumbar disc pain.

- Decreased pain with certain positions, such as sitting in a reclining position or lying down with a pillow under the knees, or using a pillow that maintains the neck’s natural curvature during sleep.

The amount of chronic pain—referred to as the baseline pain—is quite variable between individuals and can range from almost no pain or just a nagging level of irritation, to severe and disabling pain.

Chronic pain from degenerative disc disease that is severe and completely disabling does happen in some cases, but is relatively rare.

Diagnosing Degenerative Disc Disease

The following process is typically used to diagnose degenerative disc disease:

- A medical history is collected that details current and past symptoms of neck or back pain, including when the pain started, how often pain occurs, where pain is felt, and the severity of pain and its impact on mobility. A medical history may also include information on sleep and dietary habits, exercise and activity level, and how symptoms are eased or worsened by activity or posture.

- A physical exam is conducted, which may include feeling along the spine for abnormalities (palpation), a reflex test, and/or a range of motion test that includes bending the spine forward, backward, or to the side.

- An imaging test may be ordered in some cases to find or confirm disc degeneration in the spinal column. An MRI scan is usually used for suspected disc degeneration, which can show disc dehydration, tears or fissures in the disc, or a herniated disc. A dehydrated disc may be referred to as a dark disc or black disc, because it looks darker on an MRI scan.

It is important to note that the amount of pain does not correlate to the amount of disc degeneration. Severely degenerated discs may not produce much pain at all, and discs with little degeneration can produce severe pain—a handful of studies have found prevalent disc degeneration in people not experiencing any disc pain.1,2

For this reason, a diagnosis of degenerative disc disease should always rely on a combination of a medical history, a physical exam, and any imaging tests ordered.

As a final note, it is helpful for patients to know that the amount of pain does not correlate to the amount of damage in the spine. Severely degenerated discs may not produce much pain at all, and discs with little degeneration can produce severe pain. What this means for patients is that even if they are experiencing severe pain, it does not necessarily mean that there is something seriously wrong with their spine and does not necessarily mean that they need surgery to repair any damage.

Degenerative Disc Disease Treatment Guidelines

The goals of degenerative disc disease treatment are primarily to reduce baseline pain and prevent pain flare-ups as much as possible. Most cases of degenerative disc pain are manageable through a combination of pain management methods, exercise/physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications.

Pain Management

A key focus of pain management is to improve mobility and reduce pain so daily activities and rehabilitative exercise is more tolerable. Pain from a degenerated disc is usually attributed to instability, muscle tension, and inflammation, so these causes should be addressed.

Some pain management methods are administered at home as self-care practices, including:

- Ice or cold treatment. Applying ice or a cold pack to a painful area of the spine can relieve pain by reducing inflammation, which can be helpful following exercise or activity.

- Heat therapy. Using heat from a heating pad, adhesive wrap, warm bath or other heat source can relax the surrounding muscles and reduce tension and spasms, a significant contributor to degenerative disc pain.

- Pain medications. Over-the-counter pain medications fall into two main categories—pain relievers, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), and anti-inflammatory medicines such as ibuprofen (Advil), aspirin (Bayer), and naproxen (Aleve). These medications are typically recommended for low-level chronic pain and mild pain episodes. For severe pain episodes, prescription painkillers such as muscle relaxants and narcotic painkillers may be recommended. Prescription pain medications are usually prescribed for short-term pain, as they can be highly addictive.

- TENS units. A TENS unit (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) is a small device that sends electric pulses through the body that interfere with and minimize pain signals. A TENS unit may include a device that transmits the signals directly over the skin, or a device that connects through wires to electrode pads worn on the skin, as well as a remote providing a range of frequencies for varying pain levels.

Other pain management methods need to be administered by a qualified health professional, such as:

- Manual manipulation. A chiropractor or spine specialist can manually adjust the spinal structures to relieve muscle tension, remove pressure from a nerve root, and relieve tension in the joints. Manual manipulation can provide temporary pain relief and improved mobility, and for some patients has been shown to be as effective as pain medications.1

- Epidural Steroid Injections. A steroid injected around the spine’s protective outer layer can provide temporary pain relief, which helps to improve mobility. Injection treatments may be recommended prior to a physical therapy program, so exercises can be effectively completed with minimal pain.

In many cases, trial-and-error is needed to find which types of treatment work best. Due to the long-term nature of degenerative disc disease, preferred pain management methods may change over time.

Exercise and Physical Therapy

The goals of exercise are to help the spine heal and prevent or reduce further recurrences of pain. An exercise program for degenerative disc pain will typically include:

- Stretching. Targeted stretches are useful for decreasing tension and improving flexibility in the spinal muscles. For cervical disc pain, stretching muscles in the neck, shoulders, and upper back can relieve pain; stretching muscles in lower back, hips, pelvis, and the hamstring muscles can help alleviate low back pain.

- Strengthening exercises. Conditioning the muscles to better support the cervical or lumbar spine can help provide added support to a degenerating spinal segment, reducing pain and instability.

- Aerobic exercise. Regular aerobic exercise is important for maintaining healthy circulation and keeping the joints and muscles active. Aerobic exercises elevate the heart rate, increasing the flow of nutrients and oxygen throughout the body, including to the spinal structures. Low-impact options are recommended for pain worsened by jostling or jolting motions, and may include a stationary bike, an elliptical machine, or water aerobics.

An additional benefit of exercise is that it can help reduce pain naturally, as it releases endorphins that serve as the body’s natural pain reliever.

Exercises are best done in a controlled, progressive manner under the guidance of a physical therapist, physiatrist, chiropractor, or other appropriately trained healthcare professional.

Lifestyle Modifications

Small, meaningful changes to daily routines can help improve overall health, which can in turn improve spine and muscle health. Some examples include:Exercises for DDD

- Avoiding nicotine

- Avoiding excess alcohol

- Drinking plenty of water

- Incorporating movement into a daily routine and avoid staying in one position for too long. For example, stand up to stretch and walk around every 20 to 30 minutes instead of sitting for a prolonged period.

- Use ergonomic furniture to support the spine, such as ergonomic desk chairs, a standing desk, or special neck pillows

The focus of this part of treatment is to provide education and resources that help develop a healthy lifestyle, minimizing stress on the spinal structures that can cause or contribute to pain.

Surgical Treatments for Degenerative Disc Disease

Surgery to address degenerative disc disease is usually only recommended if pain is severe and non-surgical treatments, such as pain medications and physical therapy, are ineffective. The goal of surgery is to alter the underlying mechanisms in the spine causing pain, such as excessive micro-motion, inflammation, and/or muscle tension.

Nonsurgical treatments are typically suggested for no less than 6 to 12 weeks before surgery is considered, although in most cases nonsurgical treatments are used for much longer. It is estimated that only between 10% and 20% of lumbar disc degeneration cases and up to 30% of cervical disc degeneration cases are not successfully treated using nonsurgical methods, and warrant surgery to relieve pain and improve mobility.1

Considerations Before Spine Surgery

There are several factors to consider before opting for surgical treatment if it is recommended, including:

- Recovery process. The recovery period following spinal surgery can consist of a combination of physical therapy, pain medications, or wearing a back or neck brace

- Lifestyle considerations. The everyday lifestyle changes needed for either non-surgical or surgical treatment may be considerable. In the case of surgery, a long recovery process may require significant time off from work. Additionally, regular physical therapy, and pain management will be required for optimal results.

- Imaging evidence of disc degeneration. Spinal surgery for degenerative disc pain is typically only recommended if an imaging scan correlates to the specific cause of pain, and even then outcomes are not always predictable.

Spinal surgery is always elective, meaning it is the patient’s choice whether or not to have the procedure. A spinal fusion is the most common procedure used for degenerative disc pain. In recent years, artificial disc replacement has become more widely used as devices and surgical methods have improved.

Spinal Fusion for Degenerative Disc Disease

During a spinal fusion surgery, two adjacent vertebrae are grafted together to alter the underlying mechanisms causing pain. A fused joint eliminates instability at a spinal segment, reducing pain caused by micro-motions, muscle tension, and/or inflammation. Joint fusion can also allow for a more thorough decompression of pinched nerves.

A spinal fusion procedure typically consists of the following steps:

- Under general anesthesia, an incision is made to approach the spine. For a cervical fusion, the incision is usually made in the front of the neck. For a lumbar fusion, an incision may be made in the back, front, or side of the body.

- Muscles surrounding the spine are cut away or pushed to the sides to access the spine.

- The degenerating disc is removed from the disc space.

- A bone graft and/or instruments are implanted across the disc space to stabilize the spinal segment and encourage bone growth.

- The spinal muscles are replaced or reattached, and the incision site is closed with sutures.

A fusion surgery sets up the mechanisms for bone growth, and the fusion occurs in the months following the procedure. For this reason, the complete recovery process from a fusion surgery can last up to a year, although a majority of patients are back to their regular activities within six weeks.

Following surgery, use of a back or neck brace may be advised to keep the spine stabilized and to minimize painful movements that can undermine the healing process. Additionally, physical therapy is usually recommended to condition the muscles to better support the spine, and pain medications are prescribed to manage post-surgical pain.

Artificial Disc Replacement Surgery

Degenerative disc pain can also be significantly reduced or eliminated by implanting a device that mimics the natural support and motion of a spinal disc in a procedure called Artificial Disc Replacement (ADR). Unlike a spinal fusion, this procedure is intended to maintain motion at a spinal segment after surgery.

In this procedure:

- The spine is approached through a small incision under general anesthesia. During a cervical ADR, the incision is usually made in the front of the neck; during a lumbar ADR, the incision is usually made in the back directly over the spine.

- The muscles are moved to the side or cut away from the spine.

- The degenerated disc is removed entirely, as is any degenerated portions of the spinal joints or adjacent vertebrae in the disc space.

- The artificial disc is inserted into the disc space using x-ray imaging to guide the device. Some devices also include metal plates that are attached to either vertebrae facing the disc space.

- The muscles surrounding the spine are reattached, and the wound is closed.

Artificial discs are typically made of metal or plastic materials. The recovery process from an artificial disc replacement usually consists of a combination of pain medications, physical therapy, and possibly wearing a back or neck brace. Recovery from this procedure can take up to 6 months.

Orthopedic & Sports Medicine Center of Oregon is an award-winning, board-certified orthopedic group located in downtown Portland Oregon. We utilize both surgical and nonsurgical means to treat musculoskeletal trauma, spine diseases, sports injuries, degenerative diseases, infections, tumors and congenital disorders.

Our mission is to return our patients back to pain-free mobility and full strength as quickly and painlessly as possible using both surgical and non-surgical orthopedic procedures.

Our expert physicians provide leading-edge, comprehensive care in the diagnosis and treatment of orthopedic conditions, including total joint replacement and sports medicine. We apply the latest state-of-the-art techniques in order to return our patients to their active lifestyle.

If you’re looking for compassionate, expert orthopedic surgeons in Portland Oregon, contact OSM today.

Phone:

503-224-8399

Address

1515 NW 18th Ave, 3rd Floor

Portland, OR 97209

Hours

Monday–Friday

8:00am – 4:30pm