Artificial Disc Replacement (ADR)

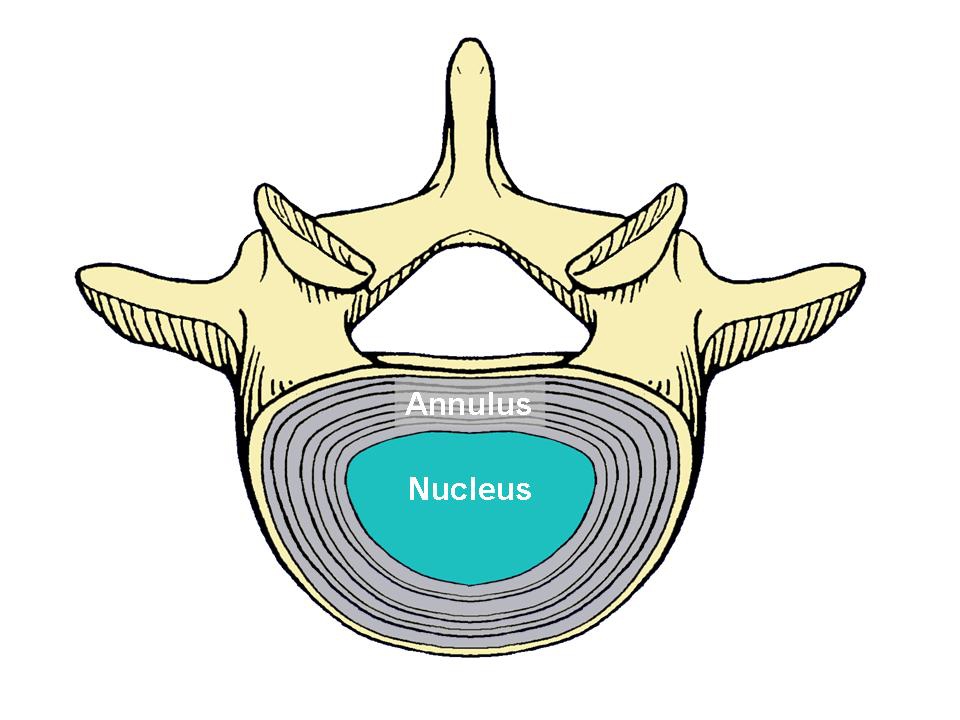

The disc is the soft cushioning structure located between the individual bones of the spine, called “vertebra.” It is made of cartilage-like tissue and consists of an outer portion, called the annulus, and an inner portion, called the nucleus (Figure 1). In most cases, the disc is flexible enough to allow the spine to bend.

An artificial disc (also called a disc replacement, disc prosthesis or spine arthroplasty device) is a device that is implanted into the spine to imitate the functions of a normal disc (carry load and allow motion).

There are many artificial disc designs classified into two general types: total disc replacement and disc nucleus replacement. As the names imply, with a total disc replacement, all or most of the disc tissue is removed and a replacement device is implanted into the space between the vertebra. With a disc nucleus replacement, only the center of the disc (the nucleus) is removed and replaced with an implant. The outer part of the disc (the annulus) is not removed.

Artificial discs are usually made of metal or plastic-like (biopolymer) materials, or a combination of the two. These materials have been used in the body for many years. Total disc replacements have been used in Europe since the late 1980s. The most commonly used total disc replacement designs have two plates. One attaches to the vertebrae above the disc being replaced and the other to the vertebrae below. Some devices have a soft, compressible plastic-like piece between these plates. The devices allow motion by smooth, usually curved, surfaces sliding across each other.

Most nucleus replacement devices are made of plastic-like (biopolymer) materials. One such material is called hydrogel. This material expands as it absorbs water. The device is placed into the nuclear cavity of the disc and hydrates to expand and fill the cavity. The device is compressible and by this means, allows motion, much like a normal disc nucleus. Another design consists of a piece of a plastic-like material that coils around to fill the nuclear cavity. No nuclear replacement devices are available for use in the United States at this time, even as a part of an FDA-approved study.

There are also disc replacements designed for use in the cervical spine (the neck). These devices have only been used a relatively short time, and several are currently undergoing evaluation in FDA-approved trials in the United States.

Who needs an artificial disc?

The indications for disc replacement may vary for each type of implant. Some general indications are pain arising from the disc that has not been adequately reduced with non-operative care such as medication, injections, chiropractic care and/or physical therapy. Typically, you will have had an MRI that shows disc degeneration. Often discography is performed to verify which disc(s), if any, is related to your pain. (Discography is a procedure in which dye is injected into the disc and X-rays and a CT scan are taken. See the NASS Patient Education brochure on Discography for more information.) The surgeon will correlate the results of these tests with findings from your history and physical examination to help determine the source of your pain.

There are several conditions that may prevent you from receiving a disc replacement. These include spondylolisthesis (the slipping of one vertebral body across a lower one), osteoporosis, vertebral body fracture, allergy to the materials in the device, spinal tumor, spinal infection, morbid obesity, significant changes of the facet joints (joints in the back portion of the spine), pregnancy, chronic steroid use or autoimmune problems. Also, total disc replacements are designed to be implanted from an anterior approach (through the abdomen). You may be excluded from receiving and artificial disc if you previously had abdominal surgery or if the condition of the blood vessels in front of your spine increases the risk of significant injury during this type of spinal surgery.

Back pain is sometimes produced by an injured or degenerated disc. To treat this condition, alternatives to disc replacement include fusion, nonoperative care or no treatment. Typically, surgery is not considered for disc-related pain unless the pain has been severe for a prolonged period (typically over six months) and the patient has gone through nonoperative treatments (such as active physical therapy, medication, injections, activity modification and/or spinal manipulation).

Traditionally, the operative treatment for disc pain has been spinal fusion. This is a surgical procedure in which disc tissue is removed and bone is placed between the vertebral bodies. The goal of this surgery is to fuse the vertebra around the disc that is causing pain. It is thought that by removing disc tissue and eliminating movement, the pain will be significantly reduced.

A normal healthy spine allows motion at each of the discs throughout the spine. Ideally, your surgeon would like to restore your spine to this normal state. Currently the treatment for many painful spinal conditions is fusion, which eliminates motion of the painful spinal segment. Artificial discs are designed to allow motion after surgery that is as normal as possible.

With fusion there also is a possibility that the fusion of one part of the spine forces the discs and vertebra above and/or below to carry more load and motion. This may result in more wear and tear than normal. The artificial disc may significantly reduce this risk.

Another potential advantage of disc replacement is a more rapid return to activities than occurs after fusion surgery. Fusion patients have limited activities during the time required for the bone graft to grow into a solid mass. Because one of the goals of artificial discs is motion, patients are encouraged to return to motion early, although at a gradual progression. Although artificial discs offer several advantages over fusion, this is a relatively new technology with no long-term randomized, controlled clinical study results. Fusion has a long-standing record of success in permanently correcting problems in the fused motion segment. Discuss both options thoroughly with your health care provider before deciding which procedure is best for you.

The type of artificial disc to use, if any, depends on the cause of your back and/or leg pain, the severity of the problem and the training of your surgeon. A nucleus replacement may be an option for patients with early stage symptomatic disc degeneration where the annulus is in good condition. These devices also may be implanted after a discectomy involving the removal of a large amount of disc tissue. In discs with more severe degeneration, a total disc replacement may be indicated.

As with any surgery, there are risks associated with disc replacement. The complications when using artificial discs are similar to those associated with anterior spinal fusion. Possible complications include but are not limited to: infection, injury to blood vessels, nerve injury, dislodgement or breakage of the device, wear of the device materials, continued or increasing pain, development of new pain, sexual dysfunction, injury to urologic structures and death. Discuss these risks with your surgeon before deciding to have an artificial disc implanted.